Art and technology have consistently shared a permanent relationship in human history, where creatives have relied on brushes, paints, stencils, spraypaint, and other physical mediums to express their works.

With the growth of emerging technologies, artists have begun exploring new mediums to communicate complex, abstract ideas to audiences with methods never experienced in previous exhibitions.

The meteoric rise of AR-powered art comes amid the debut of several artists, including the anonymous Mexxr, who released the world’s first AR art gallery using Google Chrome browser’s Play Services for AR.

Artists are also exploring additional technological mediums for creative expression, including artificial intelligence (AI), deepfakes, and non-fungible tokens. Events such as the DEEEP Art Fair at the Art in Flux in East London showcased the future of Metaverse artworks taking shape in the industry.

The following is one of a series of conversations set to take place for XR Today on the role of XR in the art space, and how this emerging technology is impacting the lives of content creators across the world.

XR Today spoke to Yoyo Munk, Chief Science Officer for Tin Drum, a global mixed reality (MR) studio. Munk was also the director of the ‘Medusa’ art exhibit at the London Design Festival, which took place at the Victoria and Albert Museum in September.

Can you tell us about the collaboration you had with Mr Fujimoto on the art installation? What was the journey and process taken to build this visual masterpiece?

Yoyo Munk: This piece started with a chance meeting between Todd Eckert, CEO of Tin Drum, and Ben Evans, Chair of the London Design Festival.

We were working as Tin Drum using MR as a medium, and they struck up a conversation about doing a piece of MR architecture—an experience without a physical form—with just glasses providing a space for exploration.

The world got very interesting in the last two and half years [due to the pandemic], and some of our more immediate plans had to be put on ice. We later decided the time was right earlier this year and the LDF facilitated the connection between Tin Drum and Sou Fujimoto’s atelier in Paris.

Around May this year, we began collaborating with three architects—Barbara Stallone, Francisco Silva, Adrien de Lassence—at the Sou Fujimoto Atelier in Paris. Our initial conversations were really back and forth during the lockdown, where we discussed what MR was like as a medium, its constraints, what it does and doesn’t do well, and so on, which is often easiest to physically demonstrate to people.

Due to us all being under lockdown at the time, it was difficult to travel and showcase things easily, and a lot of [our plans] had to emerge from these conversations and discussions.

The atelier later came to us with a series of concepts, slides, sketches, and other ideas they thought might be interesting, and we evaluated them based on whether they would work well in the limited medium we had. We later philosophically connected on an early idea of moving towards architecture without form.

There’s an old Louis Sullivan maxim about how ‘form follows function,’ which is an expression often used to guide the emphasis on the utilitarianism of form with ideas such as avoiding decoration for its own sake and allowing the function of the piece to inform the aesthetics.

When you start talking about a piece of architecture that doesn’t have a physical form and is completely unburdened by any utilitarian requirements such as supporting or sheltering humans, but simply existing as a space for exploration, that allows you to think, “Okay, if form follows function, now we need to think about what the function is, [especially] if it’s not a structure designed to provide shelter.”

Obviously, architecture provides a multitude of functions and is not just about separating us from the elements or providing a roof over our heads, [but] conveying a rather a distinct emotional characteristic that embodies the structures that we move through.

The way that spaces make us feel as collectives of humans inhabiting them is intrinsically part of their function, and we can explore that when we remove the physical form entirely to lean into the emotional characteristics of space.

This creates an environment designed for the inhabitant, also inhabited by a collective of humans who could be total strangers, and facilitates a connection between them informed by the nature of the surrounding space and our ideas embodied in the structure.

What was the overall theme of the Medusa art centrepiece, and why was the V&A Museum chosen as the backdrop for this MR art space?

Yoyo Munk: There were a number of themes we were really excited about regarding what we would embody within the full structure of Medusa, which, at its core, was a desire to examine the complexity of the relationship between architecture and nature.

You’ll find plenty of people who say they find inspiration in nature, whether they come from design or architecture, and so forth, but is usually expressed at a fairly superficial aesthetic level.

Which is not to say you can’t create beauty and form by observing nature and filtering that through the lens of human perception to create the structures we bring into our worlds, but there’s also a darker side to this relationship, which is that our human architecture typically exists at the expense of natural structures. When we build, we displace existing ecosystems and greatly reduce natural and non-human structures in the world to create our own architecture for us to embody.

One of the aims of this piece was to examine the complexity of that relationship between human architecture and nature, at an aesthetic and deeper level, to create a space explicitly about the displacement and destruction of natural structures for the sake of human architecture.

At the core of any piece of human architecture is a story, which [differentiates] an ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ for the structures we’ve built. Humans go inside, this is our space, which separates us from the outside.

It’s always been that same biosphere and connection of living forms, where humans have been a part of that structure, but we get very romantically attached to the idea that we exist outside of nature, and that our technology and ability to shape the forms of shelter can replace existing ecosystems with spaces we’ve designed for our own use. This really lies at the soul of what architecture is all about.

Having internalised this, we’ve arrived at a point in the history of our species where we will have to spend the rest of our time on this planet working our way through the consequences that have built up over time as a result of that story.

Using the Raphael Court [at the V&A Museum] was a simple answer: when the Universe threw [us] an opportunity, we had to do everything possible to make that happen.

It was offered to us as a part of our association with the London Design Festival, and as soon as it was on the table, we jumped on the opportunity as the Raphael Court is a perfect thematic fit for the piece.

Raphael was an artist at the height of the High Renaissance, which was a time for art where there was this pure celebration of the grandeur of human accomplishment.

There was this sense of magnificence in what humans could create, and these masterpieces by Raphael, presented in this space mimicking the structure and form for the Sistine Chapel, provided a critical real-world context for Medusa.

It’s essentially a physical monument to human grandeur that evokes a time before we’d truly internalised or conceptualised what the eventual consequences of that solipsism and narcissism at the collective level would ultimately create for us.

In Medusa, we have this non-existent piece of virtual architecture inside the room shared between people wearing the headsets, designed to be reflective of a spectrum of natural structures within this extraordinary backdrop, to contextualise our work in the greater space of how humans sought to elevate themselves.

I was a really big fan of Greek history back in university and noticed how the artform interacted with people at the exhibit by almost swallowing them whole, which was very compelling as I tried to piece together the symbolism behind it, namely how Medusa ‘ossifies’ those who look upon Her.

Yoyo Munk: Certainly, one of the things we were really playing with here was the idea of physicality, or sense of it without physical form. Gazing upon the mythological Medusa transformed the living into stone, a transfiguration of physical form mediated through light, and in our piece, we’re trying to create the impression of physical form and solidity using light.

It was a way of nodding to the idea of creating the sense of physical space, that there is this thing here, swallowing people, moving around them, and inhabiting this space, but constructed entirely out of light. There’s no real solidity to it.

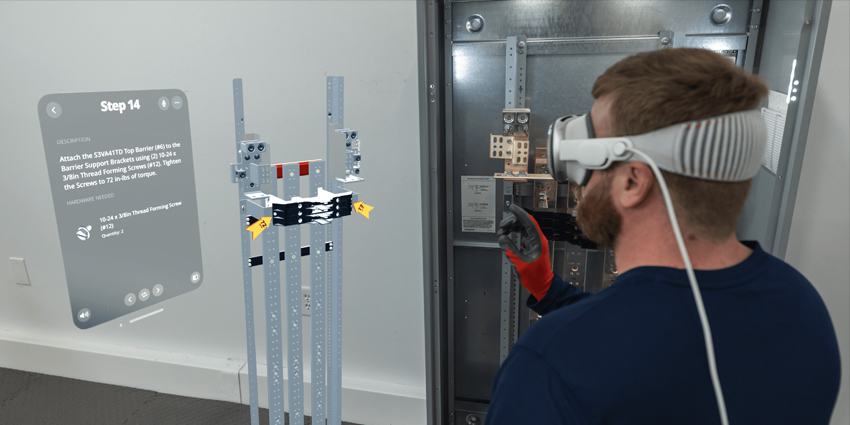

Moving into the nuts and bolts of the exhibition, can you tell us about the Nreal headsets? What kinds of technology were essential to create the exhibit, and why did you choose Nreal as your hardware provider?

Yoyo Munk: We’re fairly early in the days for AR, stereoscopic headsets, and an initial question to ask would be why one should use AR glasses rather than tablets for the experience, as that would generally be the way more people would choose to experience AR.

An important theme we wanted to connect with was reducing barriers between the audience and people inside the space. It was not supposed to be this isolated, solitary experience, and the way you inhabit it, consciously or not, is informed by how you observe others sharing the same structure with you.

As soon as you put a [tablet] in front of viewers, this creates a familiar partition—a physical object, even if it’s a camera passing through, already switches people into the idea they’re not really seeing a person, but rather a potential picture of the person.

One thing I really enjoyed about MR glasses in general, in addition to things such as stereoscopic depth, is the tighter connection to sensory perception, which minimises the barrier between audiences inhabiting the space together.

Despite being much more challenging to put on an AR-based headset compared to screen-based AR, the advantages are worth it, namely how we can connect with and foster connections between audiences.

When you say you would like to use an AR headset, there aren’t a tonne of options at this point. We’ve done previous projects with the Magic Leap One and HoloLens 2, but this is our first using the Nreal Light, and I would say Nreal was an attractive device for a number of reasons.

It has a very high-quality display and fairly simple optical design, using a traditional birdbath combiner with a regular mirror in it. It’s a design that has been around for a long time and works exceptionally well.

When you put a nice bright micro OLED projector at one end of the that chain, you get a very clear, robust image, and when you compare that to images you can get through, say, diffractive waveguides, it’s much clearer, sharper, brighter, and more colour accurate using a much simpler optical chain.

It’s a marvel of optical engineering that these more complex devices with diffractive waveguide options work at all, and they are truly impressive pieces of optical engineering, but I haven’t seen any evidence yet that [the industry] is at the level of sophistication to truly provide an exemplary quality display.

Also, compared to other options, because we run these large exhibitions with a massive number of people, the fact that the Nreal is a separate device detachable from the computer pack gives us quite a few options as to how we can structure our events.

When we’re running a HoloLens-based display, the whole headset is a monolithic object, meaning when the device inevitably needs to charge, we’ve lost both the display and computer.

When the display and computer pack are separate, we can have roughly double the number of phones as we have displays, and so we’re constantly cycling the glasses repeatedly through the sanitation process, but are only swapping out the computer packs for charging. This gives us quite a bit of flexibility in structuring the exhibition design.

I would also add the rather pedestrian issue of cost. Nreal is substantially easier on the wallet [than other commercially available MR headsets], especially when it comes to sourcing 70 of them.

The comparatively low cost allows things to become more tractable when working with large audiences. Our goal is always to push the boundaries of things like how many people we can get into spaces, but we can also do things that involve five people, which is still a fairly intimate crowd.

The way people interact with spaces transforms once the numbers increase to roughly 30 or so, creating a collective with an energy of its own, which constantly changes as people enter and leave the space.

It’s also less defined by individual contributions rather than what’s happening at the meta level between people in the space. If we can afford to buy more of these devices, we could run larger audiences, which has advantages as well.

Lastly, we make use of a lot of advanced technology in what we do, but we’re not really in a space where we’re trying to present ourselves as champions of technology for its own sake.

I think there’s an advantage to the familiarity and form factor of Nreal glasses, where I can hand someone a phone in a pouch, which technically contains a phone, but audiences don’t even realise.

I also give them a pair of glasses, which they put on, and are familiar with its form factor. This lowers that barrier to entry, and audiences don’t have to think so much about the technology, allowing us to have a more direct connection to the work itself compared to a more complex device where you have to explain to audiences how to use it, step-by-step.

Minimising the audience’s focus on the technological aspects is very compelling, even as they walk around, which reveals it’s equally important to pay attention to attendees rather than the art itself. This reflects how people perceive it, and one could see people even sitting together, stargazing at the experience, as it took place. Medusa began to shape those relationships as people interacted with one another and moved slowly through the exhibition, which was really interesting to notice and watch.

Yoyo Munk: Audiences would almost take on characters of their own, so when people entered the space, it was sometimes the audience that would remain in a kind of passive space, sitting on benches or standing still. When someone entered, they would often feel compelled to notice how everyone in the space was interacting, and would join this collective fabric of people in it.

But if it had been a different crowd, with everyone wandering around, they may have been compelled to walk instead. This helps us examine the nature and extent to how we individually conceive how we move through spaces.

The sense of agency we carry into our exploration of spaces is either consciously or subconsciously influenced by our perception of how others already inhabit the space, along with the implicit narrative joining the people inside that space. Some people like to just lie on the ground and stare upwards, and say they had a great time. As soon as one person lay on the ground, others would join them.

Conversely, some people even attempted to take a picture with their phones through the smart glasses, which doesn’t work well at all, but as soon as one person tries that, everyone else wanted to give it a go, creating a space where everyone frustratingly tries to take a picture of something.

It was as if the experience was deliberately resistant to being ‘Instagrammable’, and that this was not about creating a space to preserve moments of yourself in it.

Regarding the rise of AR as a medium of artistic expression, how does it compare with other artistic mediums, and why has Tin Drum chosen to promote it?

Yoyo Munk: I think there are obvious links between AR as a medium [of art] and other media that have come before it, such as sculpture, architecture, and film, and generally, the video gaming industry is the more obvious sector for people working with AR.

I typically see AR as a medium with a number of interesting constraints associated with it, and am fascinated with the ways in which they drive creativity. As soon as you know what you can’t do with it, it pushes you to find ways you can accomplish things.

Regarding AR, and much like VR as well as other forms of interactive media, there’s a general kind of trust exercise between creators and the audiences experiencing it, because you’re dealing with free viewpoints spaces where, if done correctly, allows creators to shape general experiences that do not impose specific visions or guidelines on how it must be explored or inhabited.

You’re really entering this collaborative space between yourself and the audience, which includes how things are organised on a table, which people may use in different ways or take completely differently than your initial thoughts. I think that trust exercise is really interesting, and I’m drawn to that space, because it’s one that’s really hard to do.

It’s very easy to get into these kinds of garden path experiences where technically the exhibit is interactive, but also there’s a ‘right’ way to do this, or you have to push this button and pull this lever kind of instructions, which is less interesting to me because it functions like a puzzle or pin space.

The idea of arriving at a sense of a truly collaborative expression, where the audience is as much involved with the creation as the people actually writing the code for it, feels exciting and interesting.

I think a lot of our journey through technology and interactive storytelling has leaned heavily into concepts of power fantasies and the emphasis of the individual, where you can do things you wouldn’t do otherwise, but these experiences are very isolated and you’re not entering these spaces as yourself, but as an idealised avatar of how someone may perceive you.

There’s nothing wrong with that, but there’s also an aspect that feels slightly insidious when connecting with other people inside the space. When you think about VR communication channels where people navigate with their avatars and wave their hands, it’s a form of a connection which is very much filtered through the [VR] medium.

You’re not really connecting with these humans as humans, but through an entirely different form of connection. As humans, we’ve engaged in numerous kinds of connections, such as writing a letter, which is different from speaking directly to others.

It’s not to say that some kinds of communication are bad compared to another, but I would generally say, especially related to collective spaces and large audiences, there are subtle and unconscious aspects to how people connect, which are difficult to translate into a limited medium.

It’s much easier just to let people see each other and connect, rather than wondering how to create an avatar that works inside this context. Regarding Medusa, there’s nothing stopping a person from producing a VR version of the piece, but I would question how to create a space where people can enter and feel as if they have a human connection with each other, which could be very difficult.

It’s quite easy with AR, because I don’t have to do anything but provide the structure for people to see each other and interact normally. One of the things that attracted us to AR spaces was the idea there was an excitement that came from working with an emerging medium, which makes you feel you’re on the forefront and trying new things.

The other aspect is oftentimes, when someone comes to see one of our pieces, it’s their first time trying MR technology, meaning they’re not arriving at this space with a preconceived notion of AR or what to expect from the experience.

A number of people that showed up at Raphael Court disappointedly expected to see an actual physical structure hanging from the ceiling, only to learn that they had to put on a pair of glasses to see the experience.

When you have the opportunity to curate someone’s first experience with a new medium, there’s a lot of opportunity and responsibility that comes with that, because you’re creating the first exposure to these kinds of pieces in the medium and are defining the preconceptions people will bring into the future.

I think that there are many different ways people have moved into this emerging medium, and I think we’re generally interested in using it to create pieces that are fundamentally about regaining a sense of human connection eroded by the sort of individualism pushed through our current era of techno-fetishism. Everyone has a ‘rectangle,’ their connection, and photos of yourself here, here, and here.

Such preoccupations have created a deep sense of isolation, paradoxically, despite all the connection our technology has allegedly enabled. Our desire is to try to subvert some of that by leaning into the ironic use of technology to create pieces that are less about the tech itself and more about the medium and how it makes people feel about themselves and each other.

I think when you see people using their devices, via headsets, mobile phones, and anything AR-enhanced or enabled, they tend to look at it through the lens of themselves. I think it’s good to have these kinds of art forms that force people to look at their environments in new lights, driven by concepts that help them see things differently outside of their individual self. For me, that’s going to be a major wake up call.

Kindly visit Tin Drum’s website for more information.